How Much Silence Is Too Much?

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

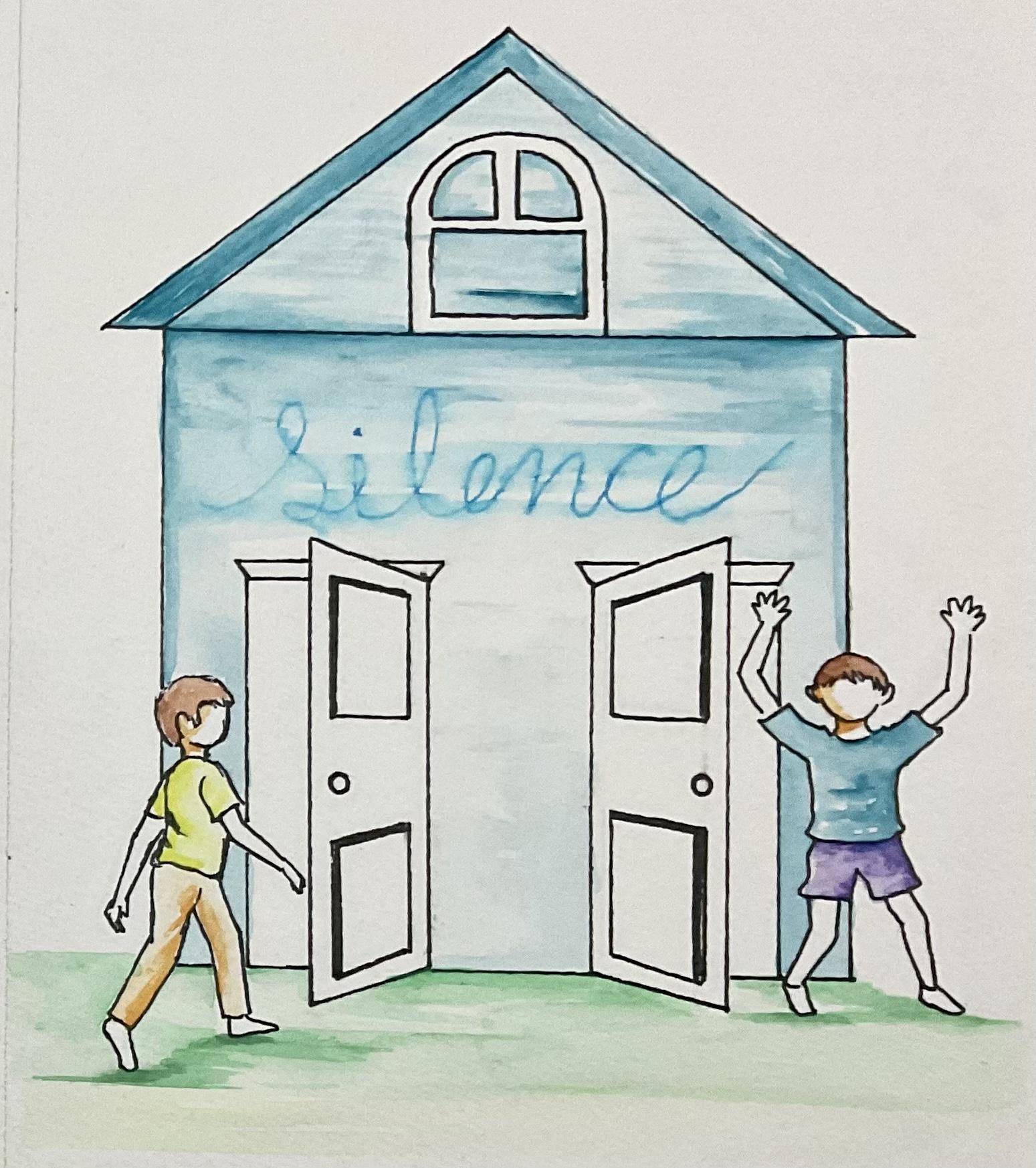

We are grateful to Rupali Bhuva for offering this hand-made painting for this reading.

Ours is a noisy country. We’ve been rebellious, insolent shouters since the beginning. We invent freak shows and circuses and casinos. Talk too loud. Our public spaces honk and whistle at us. We believe ourselves stars just awaiting a stage. We’re a people, Walt Whitman crooned, “singing, with open mouths,” our “strong melodious songs.” We chew with open mouths, too — we’re without pretense or much regard for personal space. Our latest, greatest gift to the world is a computer for your pocket that chatters at you all day long. And then there’s the past two years: political and technological churn, offense and outrage. Noise incarnate.

As much as anyone else, I fantasize about checking out. I would love to remove the pinging notifications from my days, for my mind to wander without being thrown askew by each incoming tweet. But visions of total unplugging also seem a bit grotesque. Even if we can still shut our eyes and cover our ears, become details of the landscape, should we? Is it morally acceptable at this moment?

How much silence is too much?

Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk who was among the most influential Catholic thinkers of the 20th century, pondered this question intently. What drew him to the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky was the opportunity for a life of quiet contemplation. His greatest fantasy, he wrote, was “to deliver oneself up, to hand oneself over, entrust oneself completely to the silence of a wide landscape of woods and hills, or sea, or desert; to sit still while the sun comes up over that land and fills its silences with light.”

When his popularity as an author made it more difficult to achieve solitude, he retreated even further, living for long stretches by himself in a toolshed in the hills of the monastery grounds. But the world intruded, particularly in the 1950s and ’60s, as the Cold War ramped up and a nuclear standoff seemed imminent. He began to wonder whether the life he had constructed for himself, so sustaining to his soul, justified the disengagement.

Merton did not want to contribute to what he repeatedly called the “noise” of society, but he also knew it wasn’t right to ignore his own stake in the world’s problems. What he sought instead was a “genuine and deep communication,” one achieved, he insisted, only through a continuous recharging in silence. The very element that might seem to make us bad citizens or antisocial is at the same time a prerequisite for thoughtfulness and more profound connection with others. Since most of us can’t yo-yo in and out of solitude (despite the meditation apps that promise to help us do just that), we have to live with this paradox.

Gal Beckerman is an editor at the Book Review. The excerpt above is from the NYT book review of How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in Times of Transparency by Aikiko Busch

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: What does a genuine and deep communication mean to you? Can you share a personal story of a time you communicated after recharging in silence? What helps you reconcile seeking solitude with avoiding the trap of disengagement?