When My Father Faced An Emergency

Someone asked me once if I had ever seen my father in an emergency situation, and if I might describe how he dealt with it. At the time I replied that I had never witnessed him in any danger, or in an emergency. But later I remembered that I had. The fact of my not recalling the emergency is significant.

We were in the car. Driving to my riding lesson. At that time we lived in Big Sur, California. If you have ever had the pleasure or terror of driving the Big Sur coastline on Highway One, you will know that the two-lane road is characterized by majestic mountains on one side and steep, death-defying cliffs that plummet down to the Pacific Ocean on the other. We had an old dirty white Volkswagen Van. It was the ’70s, we were a hippy family and I was a long-legged, scraggly, mountain child, about 10 years old. I was in the backseat, free to roam around as there were no seat belts back then. My father was driving, and while it is not part of this story let me just say he was one of the worst drivers ever. He was always busy looking at the whales in the sea, or spotting hawks. Terrible.

As we drove up the coast, we passed a hitchhiker on the side of the road who had his thumb out. He was a young man with a big backpack. A traveler. My father, ever the anthropologist, was interested in travelers, and in people in general. He liked to pick up hitchhikers. He liked to have conversations with strangers. So we picked up this fellow.

A few minutes later as we were driving along the man suddenly had a knife in my father’s side. He was demanding money; he was pumping with adrenaline.

I think this qualifies as an emergency. A two-lane road with nowhere to pull over. A kid in the back seat, and it would be another 30 years before the invention of the mobile telephone.

But I never noticed. I did not see the emergency because my father’s response was to cheerfully look down at the knife and then into the eyes of the hitchhiker and say in his most droll Englishness, “Well hello, what have we here?”

He was authentically calm and amused. His interest in the desperate young man had actually increased several fold by this communication, (i.e. a knife and monetary demands). My father began to ask him questions. How had he come to be in Big Sur? How had he found himself in such a muddle? Through these questions and, more importantly, the tone of the questions, my father was listening and learning about how someone can get in such a twist. He was not applying a psychological trick or a technique. This was not a manipulation. He was not ‘trying’ to calm the guy down. He was just interested, one human being to another. His curiosity in the young man was piqued, and his inquiry reflected that. He did not see a knife… he saw a person with a story.

How would most people react? Would they fight, would they try to get the money to him right away? Would they try to trick him? What are the scenarios that immediately play out? For most of us, a knife in our side would be a moment of panic. This was an emergency. But somehow it was not. As a passenger in the back seat of the van I watched their interaction and never for one second felt fear in the car. There was no spike in the drama, no flutter of breath, no indication of danger at all. I still do not think of that afternoon as being life-threatening, though surely it was.

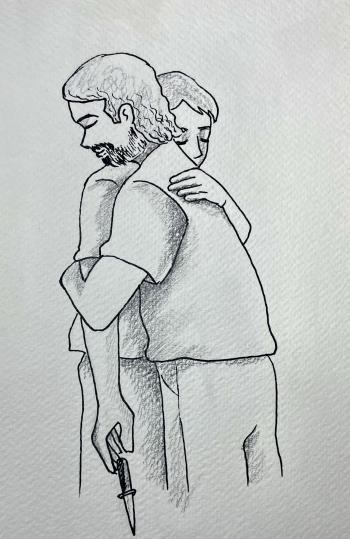

After driving another half an hour we came to a place where we would have to drop off our hitchhiker and deliver me to my horseback-riding lesson. When we pulled off the road my father opened his wallet and gave the young man a $20 bill. He wrote our home phone number on a scrap piece of paper from the floor of the car and gave the guy a hug. My father suggested that the man call if he found himself in trouble. These were not idle generosities to suggest good will. He was not faking it. The warmth and the care he felt for the traveler was genuine. I could feel that, and so, apparently, could the hitchhiker. All three of us learned a great deal from that half an hour in the VW van.

As I look back now at that situation I can only say that I hope one day to be able to see context as well as my father did. He was not young when this story took place. He was maybe 74 years along in his practice of seeing more than just the tip of the knife. I suppose it takes time to be able to respond to an acute situation with love that stems from complexity… or is it the other way around: complexity that stems from love?

Perhaps there is no beginning to that loop. I will start by noticing my reactions, and searching for wider, deeper edges to the complexity I am reacting to, responding to—and shift that into mutual learning.

Excerpted from here.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How do you understand love that stems from complexity, or complexity that stems from love? Can you share a personal story of a time you were able to respond to a dangerous situation with warmth and genuine curiosity? What helps you 'see more than just the tip of the knife'?

Add Your Reflection

10 Past Reflections

On Mar 12, 2024 Madhuri wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Mar 1, 2024 Mary Thomson wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Feb 7, 2024 rachael wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Feb 6, 2024 Anil Pandit wrote :

Evoked hearty feelings to reach such tranquility by sheer will to be helpful to anyone in need.

Post Your Reply

On Feb 6, 2024 Annie willerton wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Feb 5, 2024 Stephanie Nash wrote :

1 reply: David | Post Your Reply

On Feb 3, 2024 David Doane wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Feb 2, 2024 Jagdish P Dave wrote :

Post Your Reply

On Feb 2, 2024 Stream wrote :

What helps me see more than the tip of the knife is remembering that I am just human like any other and I have all of the fear , anger, and whatever else is behind the violent threat of the knife in me and that what I want and need is what everyone wants and needs. Love.