The Difference Between Knowledge And Understanding

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

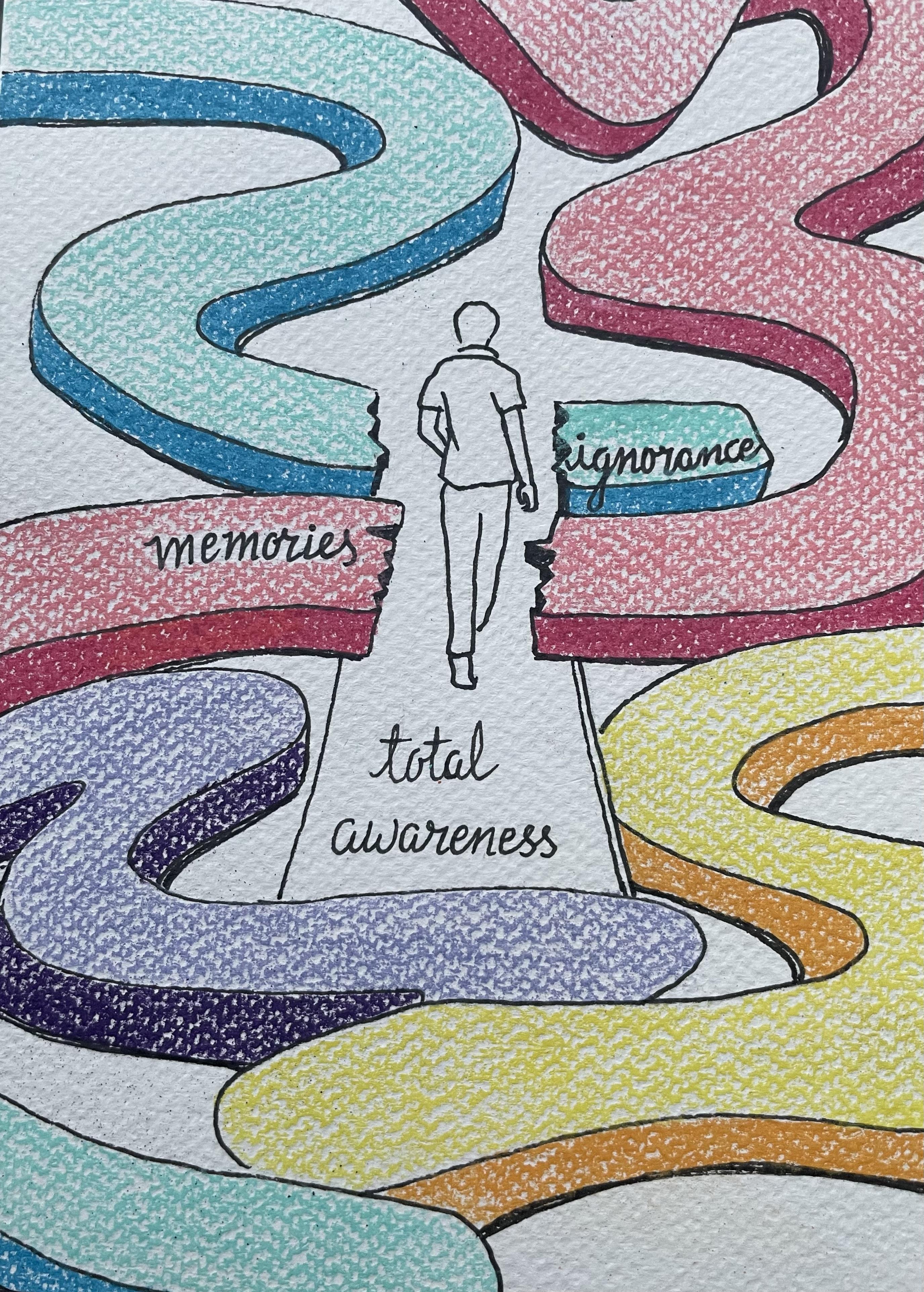

We are grateful to Rupali Bhuva for offering this hand-made painting for this reading.

Knowledge is acquired when we succeed in fitting a new experience into the system of concepts based upon our old experiences. Understanding comes when we liberate ourselves from the old and so make possible a direct, unmediated contact with the new, the mystery, moment by moment, of our existence.

Understanding is not conceptual, and therefore cannot be passed on. It is an immediate experience, and immediate experience can only be talked about (very inadequately), never shared. Nobody can actually feel another’s pain or grief, another’s love or joy or hunger. And similarly nobody can experience another’s understanding of a given event or situation… We must always remember that knowledge of understanding is not the same thing as the understanding, which is the raw material of that knowledge. It is as different from understanding as the doctor’s prescription for penicillin is different from penicillin.

Understanding is not inherited, nor can it be laboriously acquired. It is something which, when circumstances are favorable, comes to us, so to say, of its own accord. All of us are knowers, all the time; it is only occasionally and in spite of ourselves that we understand the mystery of given reality.

This discovery may seem at first rather humiliating and even depressing. But if I wholeheartedly accept them, the facts become a source of peace, a reason for serenity and cheerfulness.

In my ignorance I am sure that I am eternally I. This conviction is rooted in emotionally charged memory. Only when, in the words of St. John of the Cross, the memory has been emptied, can I escape from the sense of my watertight separateness and so prepare myself for the understanding, moment by moment, of reality on all its levels. But the memory cannot be emptied by an act of will, or by systematic discipline or by concentration — even by concentration on the idea of emptiness. It can be emptied only by total awareness. Thus, if I am aware of my distractions — which are mostly emotionally charged memories or fantasies based upon such memories — the mental whirligig will automatically come to a stop and the memory will be emptied, at least for a moment or two. Again, if I become totally aware of my envy, my resentment, my uncharitableness, these feelings will be replaced, during the time of my awareness, by a more realistic reaction to the events taking place around me. My awareness, of course, must be uncontaminated by approval or condemnation. Value judgments are conditioned, verbalized reactions to primary reactions. Total awareness is a primary, choiceless, impartial response to the present situation as a whole.

Common sense is not based on total awareness; it is a product of convention, or organized memories of other people’s words, of personal experiences limited by passion and value judgments, of hallowed notions and naked self-interest. Total awareness opens the way to understanding, and when any given situation is understood, the nature of all reality is made manifest, and the nonsensical utterances of the mystics are seen to be true, or at least as nearly true as it is possible for a verbal expression of the ineffable to be. One in all and all in One; samsara and nirvana are the same; multiplicity is unity, and unity is not so much one as not-two; all things are void, and yet all things are the Dharma — Body of the Buddha — and so on. So far as conceptual knowledge is concerned, such phrases are completely meaningless. It is only when there is understanding that they make sense. For when there is understanding, there is an experienced fusion of the End with the Means, of the Wisdom, which is the timeless realization of Suchness, with the Compassion which is Wisdom in action.

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books—both novels and non-fiction works—as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How do you relate to the difference between knowledge and understanding? Can you share a personal story of a time you had an awareness uncontaminated by approval or condemnation? What helps you build understanding?