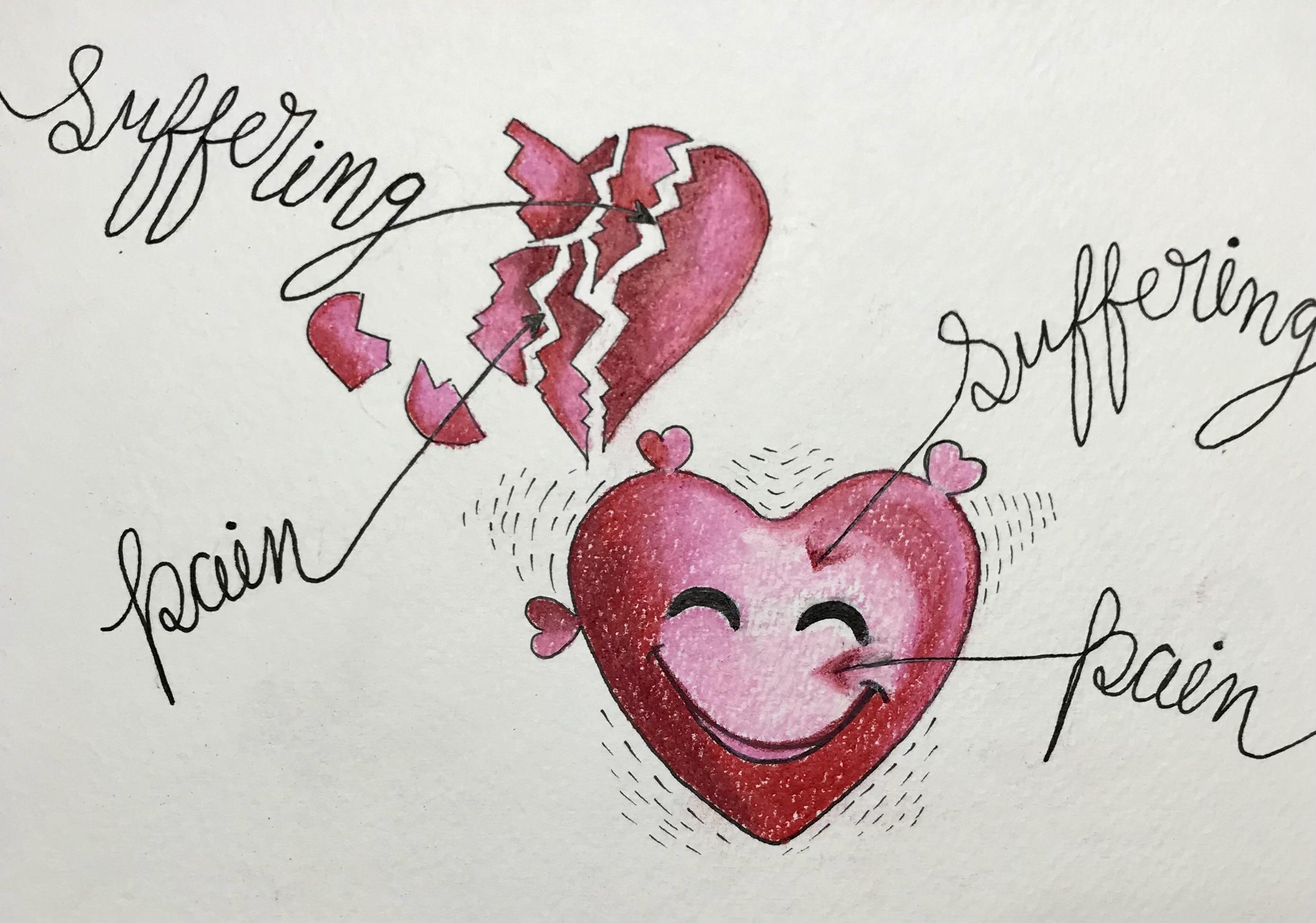

Two Types Of Heartbreaks

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

We are grateful to Rupali Bhuva for offering this hand-made painting for this reading.

A disciple asks the rebbe: “Why does Torah tell us to ‘place these words upon your hearts’? Why does it not tell us to place these holy words in our hearts?” The rebbe answers: “It is because as we are, our hearts are closed, and we cannot place the holy words in our hearts. So we place them on top of our hearts. And there they stay until, one day, the heart breaks and the words fall in.”

—Hasidic tale

Heartbreak comes with the territory called being human. When love and trust fail us, when what once brought meaning goes dry, when a dream drifts out of reach, a devastating disease strikes, or someone precious to us dies, our hearts break and we suffer.

What can we do with our pain? How might we hold it and work with it? How do we turn the power of suffering toward new life? The way we answer those questions is critical because violence is what happens when we don’t know what else to do with our suffering.

Violence is not limited to inflicting physical harm. We do violence every time we violate the sanctity of the human self — our own or another person’s.

Sometimes we try to numb the pain of suffering in ways that dishonor our souls. We turn to noise and frenzy, nonstop work, or substance abuse as anesthetics that only deepen our suffering. Sometimes we visit violence upon others, as if causing them pain would mitigate our own. Racism, sexism, homophobia, and contempt for the poor are among the cruel outcomes of this demented strategy. Nations, too, answer suffering with violence. [...]

Yes, violence is what happens when we don’t know what else to do with our suffering. But we can ride the power of suffering toward new life — it happens all the time.

We all know people who’ve suffered the loss of the most important person in their lives. At first, they disappear into grief, certain that life will never again be worth living. But, through some sort of spiritual alchemy, they eventually emerge to find that their hearts have grown larger and more compassionate. They have developed a greater capacity to take in others’ sorrows and joys, not in spite of their loss but because of it.

Suffering breaks our hearts — but there are two quite different ways for the heart to break. There’s the brittle heart that breaks apart into a thousand shards, a heart that takes us down as it explodes and is sometimes thrown like a grenade at the source of its pain. Then there’s the supple heart, the one that breaks open, not apart, growing into greater capacity for the many forms of love. Only the supple heart can hold suffering in a way that opens to new life.

What can I do to make my tight heart more supple, the way a runner stretches to avoid injury? That’s a question I ask myself every day. With regular exercise, my heart is less likely to break apart into shards that may become shrapnel, and more likely to break open into largeness.

There are many ways to make the heart more supple, but all of them come down to this: Take it in, take it all in!

My heart is stretched every time I’m able to take in life’s little deaths without an anesthetic: a friendship gone sour, a mean-spirited critique of my work, failure at a task that was important to me. I can also exercise my heart by taking in life’s little joys: a small kindness from a stranger, the sound of a distant train reviving childhood memories, the infectious giggle of a two-year-old as I “hide” and then “leap out” from behind cupped hands. Taking all of it in — the good and the bad alike — is a form of exercise that slowly transforms my clenched fist of a heart into an open hand.

Excerpted from this blog.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How have you experienced two types of heartbreaks -- brittle heart that breaks apart into a thousand shards, and a supple heart that breaks open, not apart, into greater capacity for the many forms of love? How do you relate to the notion that to make our heart supple, we have to take it all in? Can you share a personal story of a time you were able to take in 'life's little death' without an anesthetic? What helps you take all of it in, good and bad?