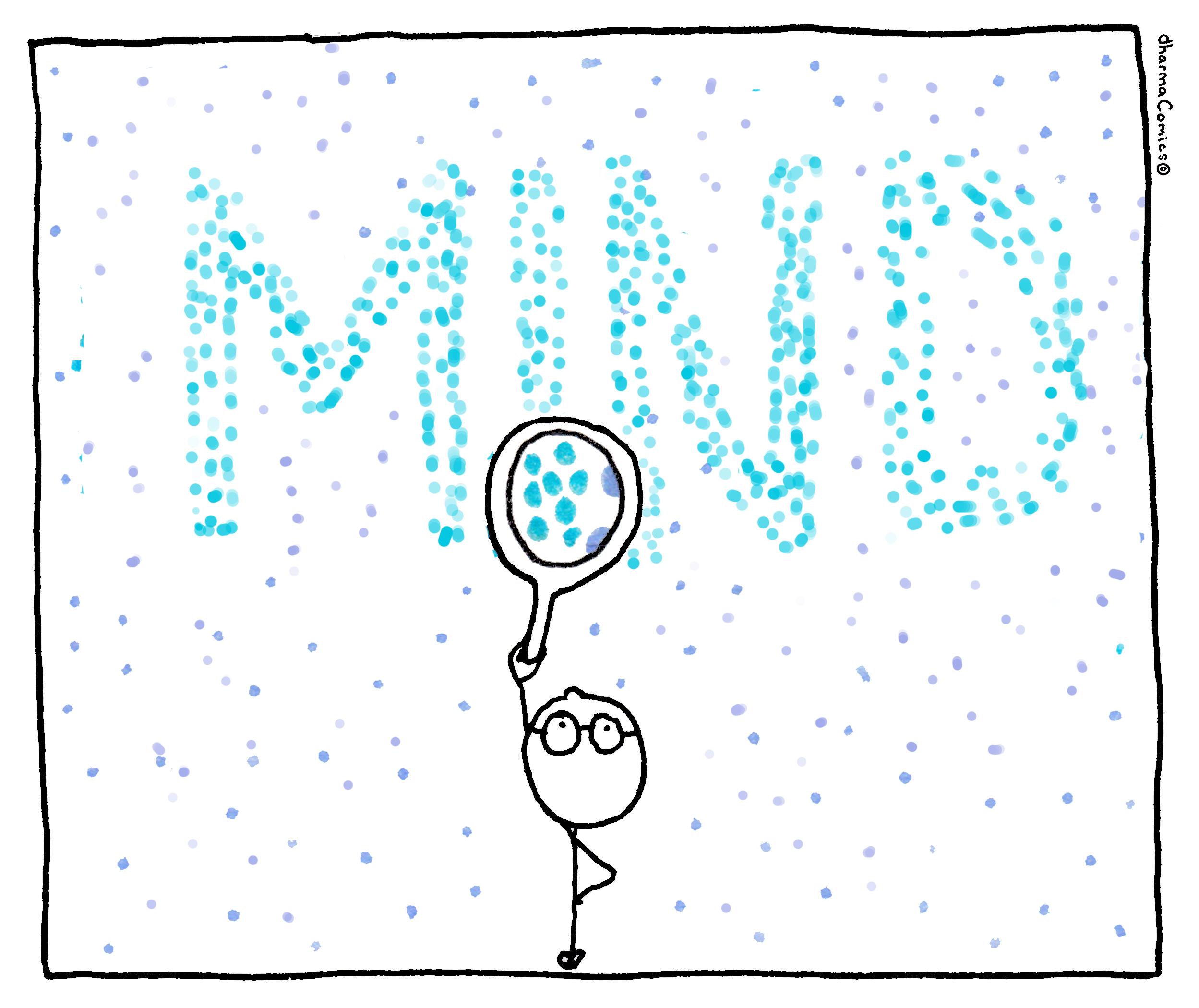

To Know Your Mind, Pay Close Attention To It

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

Certain rare and wonderful experiences are possible. But this is all we need, to take “spirituality” (the unavoidable term for this project of self-transcendence) seriously. [...]

We spend our lives lost in thought. The feeling that we call “I” — the sense of being a subject inside the body — is what it feels like to be thinking without knowing that you are thinking. The moment that you truly break the spell of thought, you can notice what consciousness is like between thoughts — that is, prior to the arising of the next one. And consciousness does not feel like a self. It does not feel like “I.” In fact, the feeling of being a self is just another appearance in consciousness (how else could you feel it?). [...]

I argue that spirituality need not rest on any faith-based assumptions about what exists outside of our own experience. And it arises from the same spirit of honest inquiry that motivates science itself.

Consciousness exists (whatever its relationship to the physical world happens to be), and it is the experiential basis of both the examined and the unexamined life. If you turn consciousness upon itself in this moment, you will discover that your mind tends to wander into thought. If you look closely at thoughts themselves, you will notice that they continually arise and pass away. If you look for the thinker of these thoughts, you will not find one. And the sense that you have — “What the hell is Harris talking about? I’m the thinker!”— is just another thought, arising in consciousness.

If you repeatedly turn consciousness upon itself in this way, you will discover that the feeling of being a self disappears. There is nothing [religious or specifically] Buddhist about such inquiry, and nothing need be believed on insufficient evidence to pursue it. One need only accept the following premise: If you want to know what your mind is really like, it makes sense to pay close attention to it.

Excerpted from a NY Times interview with Sam Harris, an American author, philosopher and neuroscientist.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: How do you relate to the notion that the feeling of being a self is just another appearance in consciousness? Can you share a personal story of a time you were of consciousness that did not feel like a self? What helps you repeatedly turn consciousness upon itself?