Giving Up is Different From Letting Someone Down

IMAGE OF THE WEEK

This inner gesture of letting go from moment to moment is what is so terribly difficult for us; and it can be applied to almost any area of experience. We mentioned time, for instance: there is the whole problem of “free time,” as we call it, of leisure. We think of leisure as the privilege of those who can afford to take time (this endless taking!)-when in reality it isn’t a privilege at all. Leisure is a virtue, and one that anyone can acquire. It is not a matter of taking but of giving time. Leisure is the virtue of those who give time to whatever it is that takes time-give as much time to it as it takes. That is the reason why leisure is almost inaccessible to us. We are so preoccupied with taking, with appropriating. Hence, there is more and more free time, and less and less leisure. In former centuries when there was much less free time for anybody, and vacations, for instance, were unheard of, people were leisurely while working; now they work hard at being leisurely. You find people who work from nine to five with this attitude of “Let’s get it done, let’s take things in hand,” totally purpose oriented, and when five o’clock comes they are exhausted and have no time for real leisure either. If you don’t work leisurely, you won’t be able to play leisurely. So they collapse, or else they pick up their tennis racket or their golf clubs and continue working, giving themselves a workout as they say.

We can laugh about it, but it goes deep. The letting go is a real death, a real dying; it costs us an enormous amount of energy, the price, as it were, which life exacts from us over and over again for being truly alive. For this seems to be one of the basic laws of life; we have only what we give up. We all have had the experience of a friend admiring something we owned, when for a moment we had an impulse to give that thing away. If we follow this impulse -- and something may be at stake that we really like, and it pains for a moment -- then for ever and ever we will have this thing; it is really ours; in our memory it is something we have and can never lose.

It is all the more so with personal relationships. If we are truly friends with someone, we have to give up that friend all the time, we have to give freedom to that friend -- like a mother who gives up her child continually. If the mother hangs on to the child, first of all it will never be born; it will die in the womb. But even after it is born physically it has to be set free and let go over and over again. So many difficulties that we have with our mothers, and that mothers have with their children, spring exactly from this, that they can’t let go; and apparently it is much more difficult for a mother to give birth to a teenager than to a baby. But this giving up is not restricted to mothers; we must all mother each other, whether we are men or women. I think mothering is just like dying, in this respect; it is something that we must do all through life. And whenever we do give up a person or a thing or a position, when we truly give it up, we die-yes, but we die into greater aliveness. We die into a real oneness with life. Not to die, not to give up, means to exclude ourselves from that free flow of life.

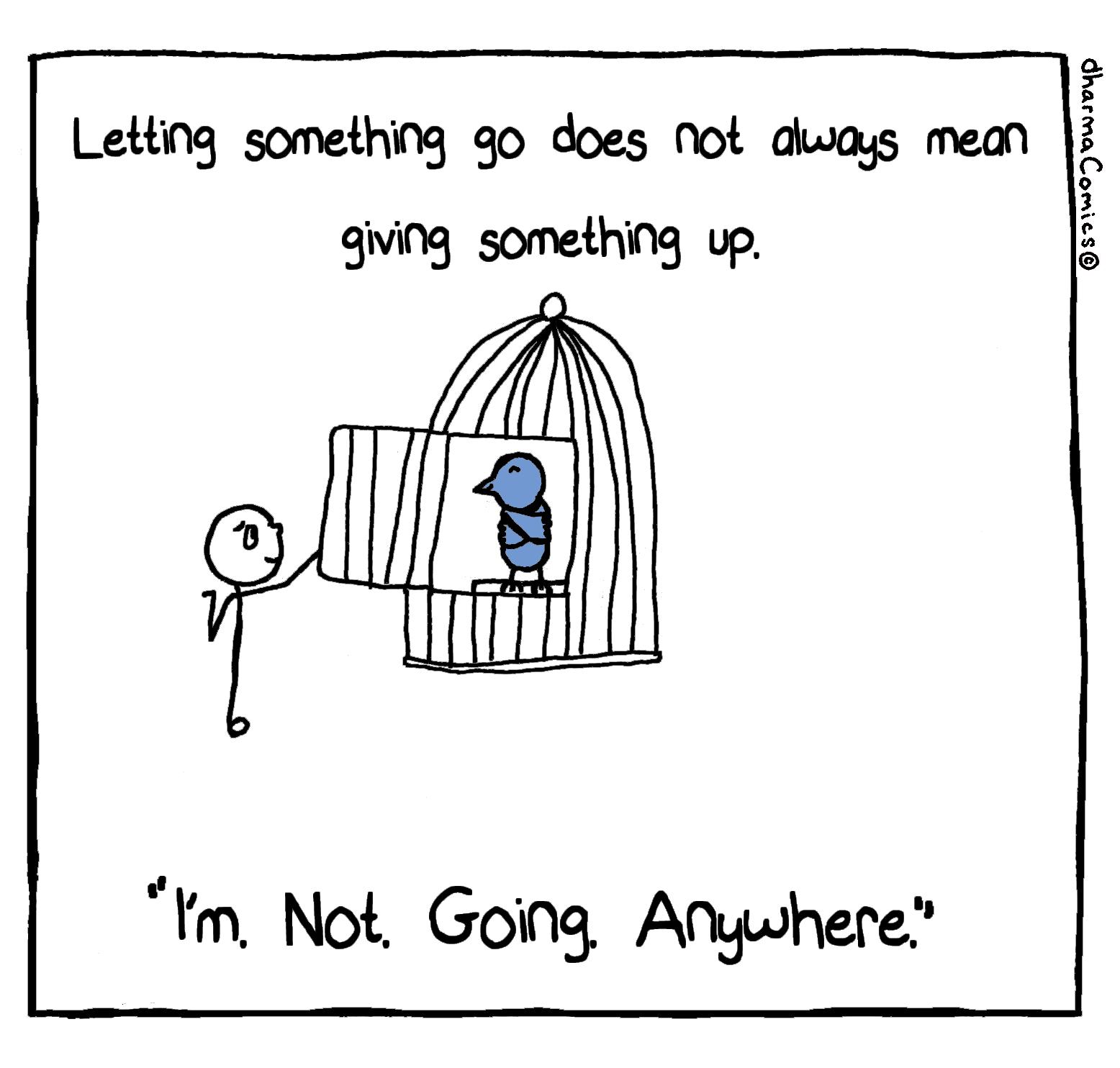

But giving up is very different from letting someone down; in fact, the two are exact opposites. It is an upward gesture, not a downward one. Giving up the child, the mother upholds and supports him, as friends must support one another. We cannot let down responsibilities that are given to us, but we must be ready to give them up, and this is the risk of living, the risk of the give and take. There is a tremendous risk involved, because when you really give up, you don’t know what is going to happen to the thing or to the child. If you knew, the sting would be taken out of it, but it wouldn’t be a real giving up. When you hand over responsibility, you have to trust. That trust in life, that faith, is the courage to take upon yourself the risk of living, and dying -- because the two are inseparable.

Brother David Steindl Rast is a Bendictine monk. You can learn more about his life in this profile, and on gratefulness.org The excerpt above is from an essay published in 1977 issue of Parabola.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: What do you understand by the author's exhortation that we must all mother each other? Can you share a personal story that illustrates giving up without letting someone down? What practice helps you experience leisure as a virtue instead of a privilege?