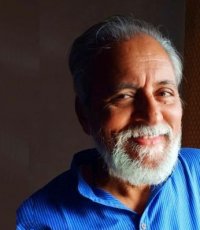

Speaker: Vivek Maru

A Global Movement for Justice: Making Rules and Systems Work for All

We are living with a global epidemic of injustice, but we've been choosing to ignore it.

More than 25 years ago, Vivek Maru told his grandmother that he wanted to go to law school. “Grandma didn't pause,” he recounted. “She said to me, ‘Lawyer is liar.’” Though he went on to fulfill that desire, Vivek soon realized that his grandmother wasn’t entirely wrong.

Vivek came to see that “something about law and lawyers has gone wrong.” Law is “supposed to be the language we use to translate our dreams about justice into living institutions that hold us together” – to honor the dignity of everyone, strong or weak. But as he told an audience on the TEDGlobal stage in 2017, lawyers are not only expensive and out of reach for most – worse, “our profession has shrouded law in a cloak of complexity. Law is like riot gear on a police officer. It's intimidating and impenetrable, and it's hard to tell there's something human underneath.”

In 2011, Vivek founded Namati to demystify the law, facilitate global grassroots-led systems change, and to grow the movement for legal empowerment around the world. Namati and its partners have built cadres of grassroots legal advocates in eight countries. The advocates have worked with more than 65,000 people to protect community lands, enforce environmental law, and secure basic rights to health care and citizenship. Globally, Namati convenes the Legal Empowerment Network, made up of more than 3,000 groups from over 170 countries who are learning from one another and collaborating on common challenges. This community successfully advocated for the inclusion of justice in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, and for the creation of the Legal Empowerment Fund, with a goal of putting $100 million into grassroots justice efforts worldwide.

Though he nearly dropped out of law school after his first year because the law felt disconnected from the problems of ordinary people he had encountered in rural villages the year earlier, Vivek stuck with it and moved to Sierra Leone soon after he graduated, just after the end of a brutal 11-year civil war. Several years before Namati, he co-founded an organization called Timap (which means “stand up”) to help rural Sierra Leoneans address injustice and hold government accountable.

Realizing that a conventional legal aid model would have been unworkable, as there were only 100 lawyers in Sierra Leone (more than 90 of which were in the capital rather than in rural areas), he instead focused on training a frontline of community paralegals in basic law and in tools like mediation, advocacy, education, and organizing. Just like a health care system relies on nurses, midwives, and community health workers in addition to physicians, he saw that justice required community paralegals (sometimes called “barefoot lawyers”) to serve as a bridge to serve the legal needs of communities and “to turn law from an abstraction or a threat into something that every single person can understand, use and shape.”

As he later recounted, “We found that paralegals are often able to squeeze justice out of a broken system: stop a school master from beating children; negotiate child support payments from a derelict father; persuade the water authority to repair a well. In exceptionally intractable cases, as when a mining company in the southern province damaged six villages’ land and abandoned the region without paying compensation, a tiny corps of lawyers can resort to litigation and higher-level advocacy to obtain a remedy.”

More significantly, he realized:

Paralegals are from the communities they serve. They demystify law, break it down into simple terms, and then they help people look for a solution. They don't focus on the courts alone. They look everywhere: ministry departments, local government, an ombudsman's office. Lawyers sometimes say to their clients, "I'll handle it for you. I've got you." Paralegals have a different message, not "I'm going to solve it for you," but "We're going to solve it together, and in the process, we're both going to grow."

And case by case and story by story, community paralegals help paint a portrait of the system as a whole, which can serve as the basis for systemic change efforts in laws and policy. “This is a different way of approaching reform. This is not a consultant flying into Myanmar with a template he's going to cut and paste from Macedonia, and this is not an angry tweet. This is about growing reforms from the experience of ordinary people trying to make the rules and systems work,” Vivek says. It’s ultimately “about forging a deeper version of democracy in which we the people, we don't just cast ballots every few years, we take part daily in the rules and institutions that hold us together, in which everyone, even the least powerful, can know law, use law and shape law.”

Vivek was named a Social Entrepreneur of the Year by the World Economic Forum, a “legal rebel” by the American Bar Association, and an Ashoka Fellow. He received the Pioneer Award from the North American South Asian Bar Association in 2008. He, Namati, and the Global Legal Empowerment Network received the Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship in 2016. He graduated from Harvard College, magna cum laude, and Yale Law School. His undergraduate thesis was called Mohandas, Martin, and Malcolm on Violence, Culture, and Meaning. Prior to starting Namati, he served as senior counsel in the Justice Reform Group of the World Bank.

Vivek is co-author of Community Paralegals and the Pursuit of Justice (Cambridge University Press). His TED talk, “How to Put the Power of Law in People’s Hands,” has been viewed over a million times. He lives with his family in Washington, DC., and though he travels a lot, he tries to spend time in a forest or other natural place every week, wherever he is.

Vivek studies capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art that mixes dance with fighting techniques as a creative form of resistance, with Dale Marcelin at Universal Capoeira Angola Center. “There’s a mischievousness and soulfulness even though you’re engaging in a life-and-death struggle,” Maru says. “I like its lesson of smiling in the face of danger.”

He is also deeply influenced by his Jain spiritual background and Gandhian principles. He is interested in a Jainism that balances an inward turn with an engagement in the outer world, citing a Jain monk who said “The test of true spirituality is in practice, not isolation . . . there is a need to strike the right balance between internal and external development.”

Join us in conversation with this exceptional leader and warrior for justice!