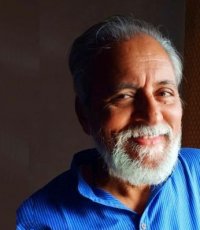

Speaker: David Bonbright

Sustainable Social Change and Philanthropy: From Transactions to Relationships

David Bonbright is a systems thinker and passionate systems changer dedicated to social change as a social entrepreneur and professional grantmaker. He is founder and chief executive of an initiative that aims to transform the fields of social investing and sustainable development. Previously, as a grantmaker and manager with Aga Khan Foundation (1997-2004), Ford Foundation (1983-1987), Oak Foundation (1988-1990), and Ashoka: Innovators for the Public (1990-1997), David sought to evolve and test innovative approaches to strengthening citizen self-organization for social justice and sustainable development as an alternative to prevailing bureaucratic, top-down models.

David Bonbright is a systems thinker and passionate systems changer dedicated to social change as a social entrepreneur and professional grantmaker. He is founder and chief executive of an initiative that aims to transform the fields of social investing and sustainable development. Previously, as a grantmaker and manager with Aga Khan Foundation (1997-2004), Ford Foundation (1983-1987), Oak Foundation (1988-1990), and Ashoka: Innovators for the Public (1990-1997), David sought to evolve and test innovative approaches to strengthening citizen self-organization for social justice and sustainable development as an alternative to prevailing bureaucratic, top-down models.While with the Ford Foundation, David was declared persona non grata by the apartheid government in South Africa for helping fund the liberation struggle. In 1990, during the final years of that decade-long struggle, he returned to South Africa and entrepreneured the development of key building blocks for civil society, including the first nonprofit internet service provider (SANGONeT), the national association of NGOs (SANGOCO), the national association of grantmakers (the Southern Africa Grantmakers Association), and enabling reforms to the regulatory and tax framework for not-for-profit organizations that were among the first laws passed by the newly elected Mandela government. He also founded and led a South African citizen sector resource center in Johannesburg relating to organizational development (the Development Resources Centre), and led the first Africa program of Ashoka: Innovators for the Public.

As a social entrepreneur, David co-founded in 2004 and serves as chief executive of Keystone Accountability (formerly ACCESS), an international nonprofit dedicated to bringing constituent feedback to social change practice. Keystone Accountability "helps organizations understand and improve their social performance by harnessing feedback, especially from the people they serve”. Keystone seeks to improve the effectiveness of organizations working in the human development field by developing new ways of planning, measuring and communicating social change that are practical and include the voices of their beneficiaries and other constituents. These include the introduction of systems for performance management and giving/social investing that realize accountability for learning in social change processes. Keystone’s original Constituent Voice™ method is now being taken up across the world.

After founding Keystone, David got an unexpected invitation to speak about his work with Nelson Mandela. He recalls sitting across from the charismatic freedom leader and talking about how much of development aid and philanthropic work runs aground because those on the receiving end have no say in it. Mandela politely listened to him for a moment and then generously shared his own experience. Mandela’s comment about the "lack of accountability by donors and NGOs to the people who are meant to benefit from the programs” serves David as a reminder ever since that "in social change, as in our personal and social lives, it is relationships that determine outcomes."

As David writes of that meeting with Mandela, "The juxtaposition that is most helpful in getting to more successful development or social change practice is doing-to versus doing-with. As President Mandela saw, powerful actors adorned in resources like money, education, technology, and access, rarely break out of their privilege to value relationships." The most effective philanthropic organizations "will demonstrate how they work to get high-trust relationships. They will measure and manage those relationships with continuous, light-touch feedback loops. They will invest heavily in the soft skills of doing-with for their frontline staff – things like coaching and appreciative inquiry."

David strongly believes in building partnerships with program beneficiaries based on equality, accountability and mutual understanding. In the field of development aid this might be a slow story because, as he believes, it requires patient observation, deep listening, and the forging of strong relational ties. About the relationship between giver and receiver he writes in one of his essays: “To be an effective giver, you need to be a good collaborator. To be an effective implementer, you need to earn the trust of those you mean to help. (…) Invest in your own learning. Your highest and best role as a philanthropist is as a steward of learning – yours and those you work with, separately and together.”

Trained as a lawyer, David has authored and co-authored a number of reports and books on the subject of philanthropy in Pakistan, indigenous philanthropy and public entrepreneurship.

He sits on the boards, advisory councils and knowledge networks of The Constant Gardener Trust, AccountAbility Forum, Alliance magazine, Allavida, Goldman Foundation Environmental Awards, the Johns Hopkins University Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, and the CIVICUS Civil Society Index.

A relentless systems changer, David‘s impact can be seen in organizations, communities, and in at least two countries at the national level, with influence traceable across the world.

Join us in conversation with this innovative thinker and changemaker!

Five Questions with David Bonbright

What Makes You Come Alive?

When I am truly connected to someone through active, deep listening. Sometimes, rarely, such connections come upon a shared moment of discovery and recognition. I live for those moments. I was doing a structured survey through a translator with plantation workers in Tanzania and I noticed a pattern in the responses that seemed contradictory. I was acutely aware of how alien I must be to the workers. I could feel their reticence and distance. I decided to break protocol and ask one respondent why the answers seemed contradictory. I could see that he was reluctant to tell me. I told him that I imagined that I looked like something pointless and useless to him and that I would think the same thing if I were him. I said that I would try to make the company understand his reality, but I could not succeed if he didn't tell me what to say. I repeated I would protect his identity. He looked deep into my eyes for a long moment, and then told me the real problem. I was able to get it fixed.

Pivotal turning point in your life?

Fresh out of graduate school I entered the South African Liberation Struggle in the very privileged position of foundation grantmaker. I had to make sense of my "profession" in a context where people were literally putting their lives on the line to create a society of equal dignity and respect for all. The activists of that struggle -- from the big name leaders to the every day heroes -- became my teachers. They had to overcome every kind of deprivation and oppression to do the work of social justice. I had to overcome my affluence, my privilege, and my white maleness to find my value and worth and contribution.

An Act of Kindness You'll Never Forget?

On his first visit to London after being released from 27 years in prison, Nelson Mandela visited a bed-ridden South African exile in her one room flat in North London. Mary Benson had written the first biography of Mandela in the early 60s, and for years had tirelessly hounded the world's media to pay attention to his situation, and to his cause. Mary was a close friend, so I got a complete blow by blow of this incredibly joyous moment for her, from the pre-visit from the security team to the amazement of her neighbors as they tried to puzzle out why the most famous person alive was visiting the little old crippled lady on the third floor.

One Thing On Your Bucket List?

To get completely and thoroughly lost in one of the world's remaining vast wild places, preferably with someone who knows how to live off the land.

One-line Message for the World?

All voices!