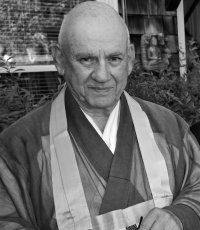

Speaker: Abbot Sojun Mel Weitsman

Walking the World of Suffering with Both Compassion and Indifference

Suzuki Roshi walked up to Mel Weitsman one day and said, “Just being alive is enough.” This became a touchstone for Abbot Sojun Mel Weitsman who, after more than 50 years of practice, continues to draw on Suzuki Roshi as his role model. He tries to be as simple as possible when he leads Zen practice, not to add things, not to expand it in some way or bring in outside sources, but to take the simplest practice and let it mature. This does not mean that he avoids talking about world events or the challenges we face at the San Francisco Zen Center, where he is a senior dharma teacher, or at the Berkeley Zen Center where he is Abbot. He merely shows how zazen (Zen sitting practice) teaches us to be alive as chaos swirls around us.

Suzuki Roshi walked up to Mel Weitsman one day and said, “Just being alive is enough.” This became a touchstone for Abbot Sojun Mel Weitsman who, after more than 50 years of practice, continues to draw on Suzuki Roshi as his role model. He tries to be as simple as possible when he leads Zen practice, not to add things, not to expand it in some way or bring in outside sources, but to take the simplest practice and let it mature. This does not mean that he avoids talking about world events or the challenges we face at the San Francisco Zen Center, where he is a senior dharma teacher, or at the Berkeley Zen Center where he is Abbot. He merely shows how zazen (Zen sitting practice) teaches us to be alive as chaos swirls around us.Weitsman says some people come to practice thinking the purpose is enlightenment. He explains that “reality is beyond your understanding, and so if you presume to have a God-like understanding, that’s arrogance…Enlightenment is a kind of arrogance.” Instead, to practice is to give up any kind of gaining mind.

Weitsman himself was not interested in enlightenment when he started his practice at the San Francisco Zen Center in 1964. Brought up Jewish, he did not have any reason, in fact, to start practice – just an open mind and an interest in learning what meditation was. He did not know what to expect, but when he faced the wall, he instinctively knew there was nothing else but this. He enjoyed meditation, but sitting zazen was painful for a long time -- until how to sit comfortably came to him. He learned from Suzuki Roshi to try to overcome attachments to physical conditions like pain so they were not creating an opposition. “As long as there is no opposition, there is no problem,” Weitsman says. “When you create opposition…it becomes a problem.”

Over time, Weitsman learned that sitting zazen is letting go. You have to let go of any gaining in your mind, to let go that sitting zazen will do any good at all. Weitsman teaches that nobody knows the purpose of practice because it is beyond thinking. He came to see that the purpose of practice was nothing – the antithesis of life, he says, because we see life in a materialistic way. So the purpose of practice is to get beyond wanting, “which is the hardest thing in the world, which is why practice is so hard.”

Weitsman says he felt like the prodigal son coming home when he first sat zazen. “When I sat down, I knew I was home.” After serving in the military, Weitsman had studied at the California School of Fine Art in San Francisco (California Art Institute) under Clyfford Still, one of the most original and influential painters of the 20th century. At age 35, he met his most significant teacher, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He gave up painting and studied with Suzuki for seven years until his death in 1971.

Upon Suzuki’s request, Weitsman opened the Berkeley Zen Center in 1967. In 1984, he received Dharma Transmission from Suzuki Roshi’s son and successor, Gyugaku Hoitsu, at Rinsoin temple in Japan and was officially installed as Abbot of Berkeley Zen Center in 1985. In 1988, he was installed as co-Abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center where he served for nine years. Although Suzuki Roshi was his role model, Weitsman says that zazen is the teacher. “Everyone receives Buddha’s teaching through zazen; that’s why zazen is so important.”

In sitting zazen, there is no Buddha, no achievement, no religion, no enlightenment. There is only reality. You have found your place in the universe and you can find it any time you want. Practice is holding the universe in the palm of your hand lightly. It is being home. “You can’t give anything to anyone that isn’t already theirs. … You can’t put something into somebody; you can only encourage it out.”

The phrase ‘Nothing special’ is one Suzuki Roshi used frequently and is the heart of practice. Weitsman says that Suzuki Roshi taught that “when we are always looking ‘over there’ for something, it is harder to appreciate where we are right now. With this understanding, grasses, pebbles, and water are always preaching the Dharma and teaching us how to act. There is nothing special to achieve. And yet, everything is special in its own unique form and way, and to be fully respected and appreciated is a form of Buddha nature” Sitting zazen is not special because it is ordinary and that makes it very special. Weitsman explains that “The selfless see the extra-ordinary quality of life in the dharmas of our ordinary world, and others suffer trying to be special while missing the special qualities of their ordinariness.”

One day Suzuki Roshi told the students that the problems they were experiencing would continue for the rest of their lives. This was not what they expected to hear. Although they laughed, they also considered what he said. Weitsman explains that improvement is okay, but it is not the goal. Some future moment is not going to be better than this present moment. Solving the problems you have now might give you a bigger problem, which is not to say you shouldn’t solve the problem, but rather, while solving the problem you shouldn’t neglect to live fully in each moment. Sacrificing this moment for a future time, we miss our lives, which is only this moment with its joys and sorrows.

Weitsman incorporates these lessons into his lectures and applies them to what is going on in America and the world today. He does not skirt the issues, but addresses them explicitly in his weekly talks, by his example, and through sitting zazen. Have the nature of determination and steadfastness, he posits: Sit still and don’t give up; have the nature of compassion: change your position without judgment; accept yourself just as you are which makes it possible to identify with others and support them. He advises using problems as tools for practice. When life is out of control, we must control our emotion. When the world is being turned upside down and we are bearing the unbearable and feeling uncertain, we must “find and maintain our composure so we can remain open and compassionate while helping to stabilize our surroundings.” We learn this when sitting zazen. We release tenseness in our bodies. We wake up to places of unresolved anger. We become aware of how we hold our well-balanced, unconditioned posture. We meet the trials and tribulations and savor the sweetness and love of our everyday activity. We learn how to be active in the world with a foundation of openness and acceptance, with concentration and non-reactivity.

We breathe. When we see one atrocity after another, we breathe deeply. This will pass. This is where we abide. We abide in our composure. Weitsman teaches that we sit in zazen and like the grass which is blown by the wind, we bend and come back up. It is more than can be explained because it is more than thinking. It is life. It is simple. It is enough.

Join us in conversation with this gifted teacher!

Five Questions with Abbot Sojun Mel Weitsman

What Makes You Come Alive?

Helping people to find their true center, the 0 point, through meditation, and proceeding from there.

Pivotal turning point in your life?

Meeting my Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki Roshi who pointed the way when I was ready.

An Act of Kindness You'll Never Forget?

My appreciation to all those who have pointed out my flaws and shortcomings, with my best interests at heart.

One Thing On Your Bucket List?

It is when the bottom of the bucket drops off.

One-line Message for the World?

Drop the self (ishness) and be compassionate to all, while striving for harmony.